The Lessons We Learned Rotating Apple Pay Certificates

When talking to engineers who have had to deal with Apple certificates at least once in their careers, be especially cautious, this topic can trigger some serious flashbacks.

In this article I describe how I implemented Apple Pay certificate rotation in a way that ultimately saved us thousands of dollars in processing costs, and how things still went sideways for 10 minutes.

Introduction

In my team, I was assigned as the DRI for Apple & Google Pay integrations. At some point I discovered that our Apple Pay certificates were due to expire in a few months, so I started delving deeper and raised the issue to make sure we had a safe, low-risk rotation plan.

Moreover, I also realized that we lacked a proper rotation plan, which occasionally caused lengthy downtimes (3.5+ hours) during certificate rotations and consequently led to processing losses for all our non-H2H merchants.

Apple Pay Certificates: The Saga

There’s a useful article from Bolt that covers the different types of Apple certificates and strategies for rotating them. It was incredibly helpful — I highly recommend reading it, and I build on some of their insights.

As a payment processor, we work with three types of Apple Pay certificates:

- Domain Verification Certificate — before a merchant can display the Apple Pay button on their website, their domain must be linked to an Apple Merchant ID and verified by Apple. This verification involves uploading a merchant-specific file provided by Apple to a designated path on the merchant’s domain. In our setup, merchants complete this verification through our Hub, which then sends the verification request to Apple’s servers via the backend.

- Merchant Identity Certificate — when a customer clicks the Apple Pay button, we send a start session request to Apple’s servers using an Apple Pay Merchant Identity certificate. This request must succeed for the Apple Pay checkout to proceed. The start session flow verifies that a valid merchant domain is associated with the entity attempting to process the transaction. In short, this is the certificate used to establish a TLS connection from your HTTP client.

- Payment Processing Certificate — after a customer initiates payment, Apple Pay encrypts the payment data using the public key associated with the certificate returned in the start session response, then transmits the encrypted payload to our servers. We use our Payment Processing certificate to decrypt the data and extract the information necessary to perform the authorization request. Encrypting the payment data in this way protects its integrity in transit and ensures that only authorized entities can process the transaction.

It’s essential to note that:

- Each Merchant ID can have up to two active Merchant Identity Certificates at the same time.

- Each Merchant ID can also have up to two Payment Processing Certificates, but only one Payment Processing Certificate may be active at a time.

We are primarily interested in the Merchant Identity Certificate and the Payment Processing Certificate, because they expire two years after creation.

Apple Cryptography

To generate new certificates, you first need to create a Certificate Signing Request (CSR). While the official documentation recommends using OpenSSL, but in our experience it has proven to be harder to work with. After generating a certificate using a CSR created with OpenSSL, the resulting hashes often didn’t match, no matter how carefully I tried to follow the algorithm. Unfortunately, the documentation leaves the details of this process unclear.

In short, the most reliable way to create a CSR is by using Apple’s Keychain Access. It is also important to note that CSRs must be generated using the Apple Worldwide Developer Relations Certificate Authority.

A few key points about CSRs:

- Payment Processing Certificates use a Prime256v1 CSR (256 bits, ECC algorithm).

- Merchant Identity Certificates use an RSA (2048) CSR (2048 bits, RSA algorithm).

- In most cases, you’ll want your private keys to follow the PKCS#8 syntax, as it’s more widely supported. The keys are generated together with the CSRs.

Hashes Verification Steps

To ensure your certificates are correctly generated, validate the hashes:

-

Generate a hash from the CSR:

openssl req -in "CertificateSigningRequest.certSigningRequest" -pubkey -noout | openssl pkey -pubin -outform DER | openssl sha256This command generates a hash from the CSR.

-

Generate a hash from the Merchant Identity Certificate:

openssl x509 -in "cert.pem" -pubkey -noout | openssl pkey -pubin -outform DER | openssl sha256This command generates a hash from the certificate.

-

Extract the key from the

.p12file and generate a hash:openssl pkcs12 -in "CommonName.p12" -nodes -out "key_tmp.pem" openssl pkey -in "key_tmp.pem" -pubout -outform DER | openssl sha256These commands extract the private key from the

.p12file and generate a hash from it.

All three hashes must be identical. If they differ, you need to start over.

Rotation

The complication in our case was that we had to rotate certificates across multiple services, namely our payment-interface backends and the decryption service. Good old microservice architecture never fails to add extra work!

For the payment services, the only certificate required is the Merchant Identity Certificate: it’s used to configure TLS for the Apple HTTP client so we can initialize payment sessions. The decryption service, additionally, uses the Payment Processing Certificate to decrypt payloads and extract the information needed to process merchants' payments.

Payment Processing Certificate

When it comes to this type of certificate, the most straightforward approach is to prioritize the new certificate when decrypting payloads.

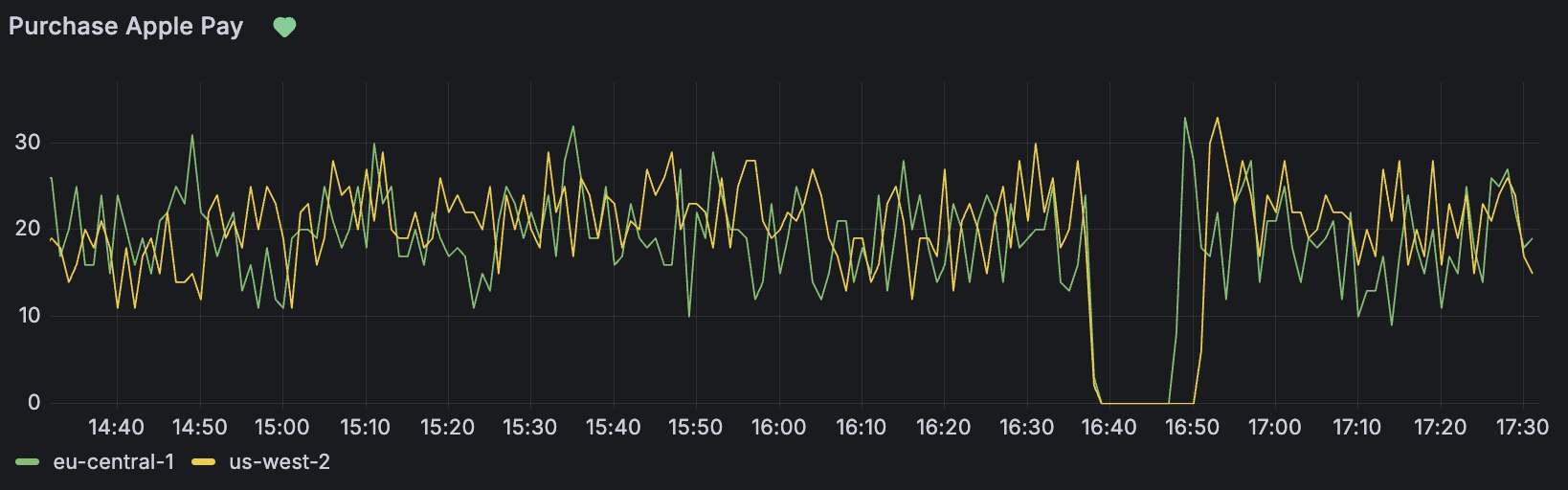

With all the systems prepared, we scheduled the rotation for early in the morning, when the Apple Pay traffic was the smallest.

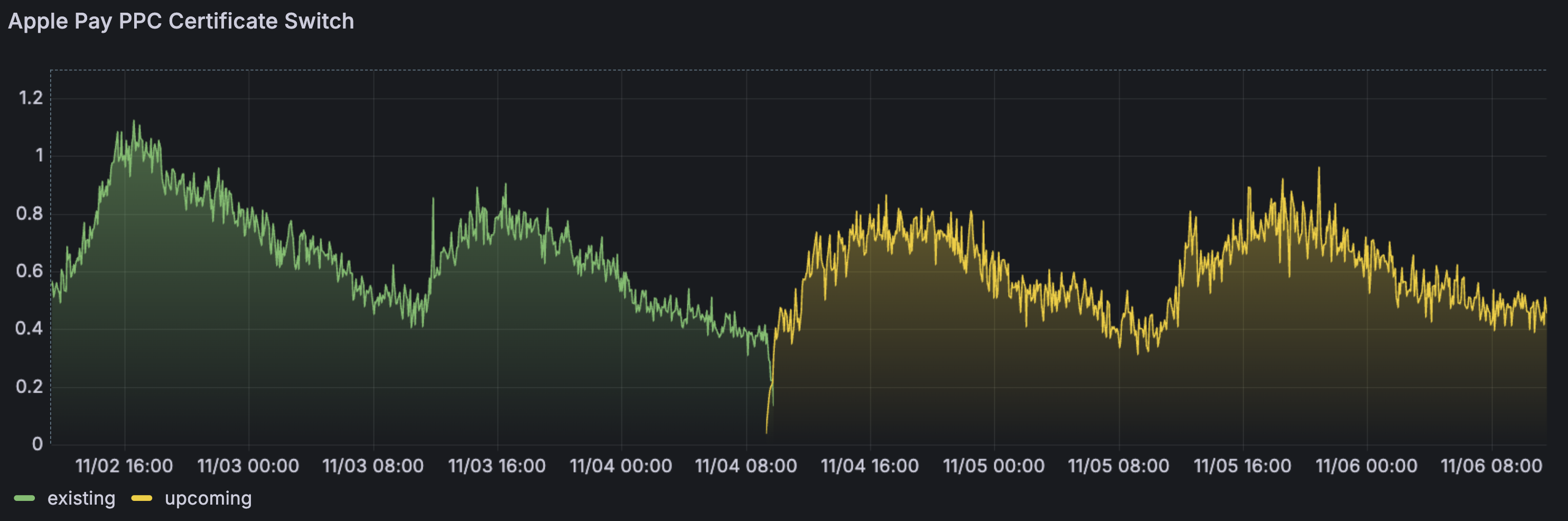

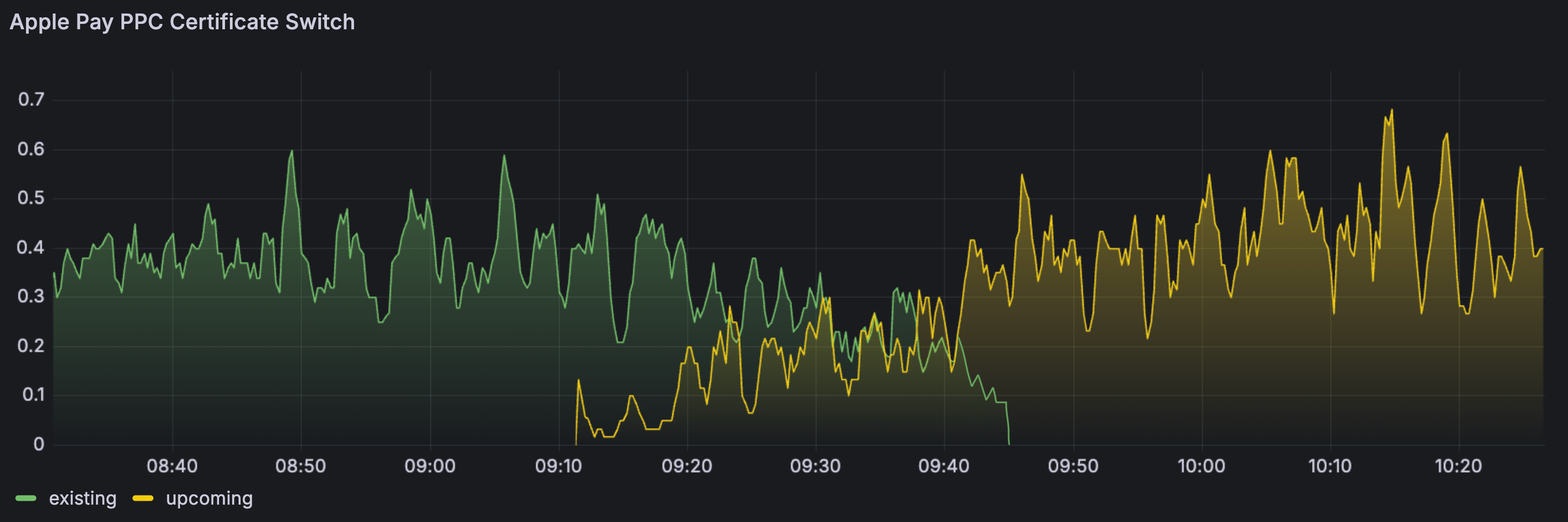

As earlier we prepared metrics for the switching process, we could easily oversee the current state of the migration. This let us know that Apple conducts a gradual rollout upon certificate revocation, which takes up to 35 minutes.

To summarize, while being the trickiest, this rotation went smoothly and without any downtime or requests loss.

Merchant Identity Certificate

As mentioned earlier, this certificate is crucial for the payment process to even begin, so we start with it. The main goal of the rotation is to switch to the new certificate seamlessly, without losing any requests in production.

Since you can have multiple active Merchant Identity certificates at the same time, we could have simply rotated them via apps' configuration files. Instead, I wanted an extra layer of safety in case something went wrong with S3 — for example, if the new certificates failed to upload.

In Go, the TLS configuration is initialized within the http.Client. Therefore, the most straightforward approach would be to use two clients.

roots := x509.NewCertPool()

roots.AppendCertsFromPEM(caPEM)

client := &http.Client{

Transport: &http.Transport{

TLSClientConfig: &tls.Config{

RootCAs: roots,

},

},

}However, I didn’t like this idea and wanted a more sophisticated solution. This led me to the concept of a dynamic TLS configuration — essentially, an http.RoundTripper that adds automatic TLS certificate failover to the http.Client. On top of that, I implemented a kind-of circuit breaker so that both certificates are always attempted. In case of repeated failures, the configuration automatically switches in favor of the failover certificate (and vice versa).

func (t *Transport) RoundTrip(req *http.Request) (*http.Response, error) {

trySecondaryFirst := t.pFailures.Load() >= t.threshold

if trySecondaryFirst {

// Try secondary first

resp, err := t.do(req, t.sLoader, &t.sTransport)

if err == nil {

return resp, nil

}

// SecondaryLoader failed, try primary

resp, err = t.do(req, t.pLoader, &t.pTransport)

if err == nil {

// PrimaryLoader succeeded, reset failure counter

t.pFailures.Store(0)

return resp, nil

}

return nil, err

}

// Try primary first

resp, err := t.do(req, t.pLoader, &t.pTransport)

if err == nil {

t.pFailures.Store(0)

return resp, nil

}

// PrimaryLoader failed

t.pFailures.Add(1)

return t.do(req, t.sLoader, &t.sTransport)

}If you noticed a potential place for improvement — feel free to contribute. Here’s how my dynamictls package can be used:

import (

"crypto/tls"

"net/http"

"github.com/vladyslavpavlenko/dynamictls"

)

// Define certificate loaders

primary := func() (*tls.Certificate, error) {

cert, err := tls.LoadX509KeyPair("primary.crt", "primary.key")

return &cert, err

}

secondary := func() (*tls.Certificate, error) {

cert, err := tls.LoadX509KeyPair("secondary.crt", "secondary.key")

return &cert, err

}

// Use with HTTP client

client := &http.Client{

Transport: dynamictls.New(dynamictls.Config{

PrimaryLoader: primary,

SecondaryLoader: secondary,

BaseTLS: &tls.Config{

MinVersion: tls.VersionTLS12,

},

Threshold: 3,

}),

}

resp, err := client.Get("https://example.com")In hindsight, the real problem was that I built the whole approach on an unchecked assumption: I expected Apple to fail at the TLS handshake level when the certificate became invalid. Instead, Apple returned an HTTP 400 error page, which completely bypassed my dynamic TLS fallback.

HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

<html>

<head>

<title>400 The SSL certificate error</title>

</head>

<body>

<center>

<h1>400 Bad Request</h1>

</center>

<center>The SSL certificate error</center>

<hr>

<center>Apple</center>

</body>

</html>This behaviour wasn’t documented, but it was still testable — I simply never tried calling Apple with an invalid/expired certificate in a realistic environment.

The certificate went invalid at a random point during its expiration day. Needless to say, the spike in errors caught me off guard. Luckily, I was able to manually update the environment variables and switch to the new certificate.

The only takeaway I had afterward — logic is not always something you can rely on; you have to test how things actually behave.

Takeaways

I originally wanted this to be a pure success story and even started writing it before the incident. What was supposed to be a resounding victory turned out to be a production fuckup — caused by building a clever system on top of an unverified assumption. That’s exactly where the most useful insights came from.

When it comes to what I learned from all this, I’d definitely highlight these points:

- Don’t ever build your systems on heuristics. If you do, at least conduct a complete and thorough testing.

- Make sure you support different certificates per environment, so the rotation process can be tested beforehand.

- Instrument the rotation itself. Track success/error rates per certificate, add alerts around expiry windows, and make the switching behaviour trackable on dashboards.

- Have a simple, documented rotation playbook. A step-by-step checklist that anyone on call can follow easily.

Thanks for reading. If this article helps you dodge a similar outage, it was worth writing.